Current sea level rise

- This article is about the current and future rise in sea level associated with global warming. For sea level changes in Earth's history, see Sea level - changes through geologic time.

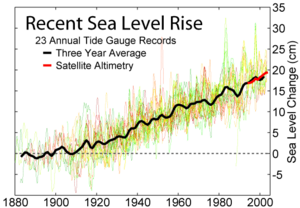

Current sea level rise has occurred at a mean rate of 1.8 mm per year for the past century,[1][2] and more recently, during the satellite era of sea level measurement, at rates estimated near 2.8 ± 0.4[3] to 3.1 ± 0.7[4] mm per year (1993–2003). Current sea level rise is due significantly to global warming,[5] which will increase sea level over the coming century and longer periods.[6][7] Increasing temperatures result in sea level rise by the thermal expansion of water and through the addition of water to the oceans from the melting of mountain glaciers, ice caps and ice sheets. At the end of the 20th century, thermal expansion and melting of land ice contributed roughly equally to sea level rise, while thermal expansion is expected to contribute more than half of the rise in the upcoming century.[8] Values for predicted sea level rise over the course of this century typically range from 90 to 880 mm, with a central value of 480 mm. Models of glacier mass balance (the difference between melting and accumulation of snow and ice on a glacier) give a theoretical maximum value for sea level rise in the current century of 2 metres (and a "more plausible" one of 0.8 metres), based on limitations on how quickly glaciers can melt.[9]

Contents |

Overview of sea-level change

Local and eustatic sea level

Local mean sea level (LMSL) is defined as the height of the sea with respect to a land benchmark, averaged over a period of time (such as a month or a year) long enough that fluctuations caused by waves and tides are smoothed out. One must adjust perceived changes in LMSL to account for vertical movements of the land, which can be of the same order (mm/yr) as sea level changes. Some land movements occur because of isostatic adjustment of the mantle to the melting of ice sheets at the end of the last ice age. The weight of the ice sheet depresses the underlying land, and when the ice melts away the land slowly rebounds. Atmospheric pressure, ocean currents and local ocean temperature changes also can affect LMSL.

“Eustatic” change (as opposed to local change) results in an alteration to the global sea levels, such as changes in the volume of water in the world oceans or changes in the volume of an ocean basin.

Short term and periodic changes

There are many factors which can produce short-term (a few minutes to 18.6 years) changes in sea level.

| Short-term (periodic) causes | Time scale (P = period) |

Vertical effect |

|---|---|---|

| Periodic sea level changes | ||

| Diurnal and semidiurnal astronomical tides | 12–24 h P | 0.2–10+ m |

| Long-period tides | ||

| Rotational variations (Chandler wobble) | 14 month P | |

| Lunar Node astronomical tides | 18.613 year | |

| Meteorological and oceanographic fluctuations | ||

| Atmospheric pressure | Hours to months | −0.7 to 1.3 m |

| Winds (storm surges) | 1–5 days | Up to 5 m |

| Evaporation and precipitation (may also follow long-term pattern) | Days to weeks | |

| Ocean surface topography (changes in water density and currents) | Days to weeks | Up to 1 m |

| El Niño/southern oscillation | 6 mo every 5–10 yr | Up to 0.6 m |

| Seasonal variations | ||

| Seasonal water balance among oceans (Atlantic, Pacific, Indian) | ||

| Seasonal variations in slope of water surface | ||

| River runoff/floods | 2 months | 1 m |

| Seasonal water density changes (temperature and salinity) | 6 months | 0.2 m |

| Seiches | ||

| Seiches (standing waves) | Minutes to hours | Up to 2 m |

| Earthquakes | ||

| Tsunamis (generate catastrophic long-period waves) | Hours | Up to 10 m |

| Abrupt change in land level | Minutes | Up to 10 m |

Longer term changes

Various factors affect the volume or mass of the ocean, leading to long-term changes in eustatic sea level. The two primary influences are temperature (because the density of water depends on temperature), and the mass of water locked up on land and sea as fresh water in rivers, lakes, glaciers, polar ice caps, and sea ice. Over much longer geological timescales, changes in the shape of the oceanic basins and in land/sea distribution will affect sea level.

Observational and modelling studies of mass loss from glaciers and ice caps indicate a contribution to sea-level rise of 0.2 to 0.4 mm/yr averaged over the 20th century.

Glaciers and ice caps

Each year about 8 mm (0.3 inch) of water from the entire surface of the oceans falls into the Antarctica and Greenland ice sheets as snowfall. If no ice returned to the oceans, sea level would drop 8 mm every year. To a first approximation, the same amount of water appeared to return to the ocean in icebergs and from ice melting at the edges. Scientists previously had estimated which is greater, ice going in or coming out, called the mass balance, important because it causes changes in global sea level. High-precision gravimetry from satellites in low-noise flight has since determined Greenland is losing millions of tons per year, in accordance with loss estimates from ground measurement. Some estimates range up to 240 km3 per year in recent years.[10]

Ice shelves float on the surface of the sea and, if they melt, to first order they do not change sea level. Likewise, the melting of the northern polar ice cap which is composed of floating pack ice would not significantly contribute to rising sea levels. Because they are fresh, however, their melting would cause a very small increase in sea levels, so small that it is generally neglected. It can however be argued that if ice shelves melt it is a precursor to the melting of ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica.

- If small glaciers and polar ice caps on the margins of Greenland and the Antarctic Peninsula melt, the projected rise in sea level will be around 0.5 m. Melting of the Greenland ice sheet would produce 7.2 m of sea-level rise, and melting of the Antarctic ice sheet would produce 61.1 m of sea level rise.[11] The collapse of the grounded interior reservoir of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet would raise sea level by 5–6 m.[12]

- The interior of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets has been (as of 2009) sufficiently high (and therefore cold) enough that direct melt there cannot cause them to melt in a time-frame less than several millennia; therefore it is likely that they will not, through melting of the interior, contribute significantly to sea level rise in the coming century. They can, however, do so through acceleration in flow and enhanced iceberg calving. Also, melt of the fringes of the ice caps could be significant, as could be sub-ice-shelf melting in Antarctica.

- Climate changes during the 20th century are estimated from modelling studies to have led to contributions of between –0.2 and 0.0 mm/yr from Antarctica (the results of increasing precipitation) and 0.0 to 0.1 mm/yr from Greenland (from changes in both precipitation and runoff).

- Estimates suggest that Greenland and Antarctica have contributed 0.0 to 0.5 mm/yr over the 20th century as a result of long-term adjustment to the end of the last ice age.

The current rise in sea level observed from tide gauges, of about 1.8 mm/yr, is within the estimate range from the combination of factors above[13] but active research continues in this field. The terrestrial storage term, thought to be highly uncertain, is no longer positive, and shown to be quite large.

Since 1992 a number of satellites have been recording the change in sea level;[14][15] they display an acceleration in the rate of sea level change, but they have not been operating for long enough to work out whether this is a real signal, or just an artefact of short-term variation.

Past changes in sea level

The sedimentary record

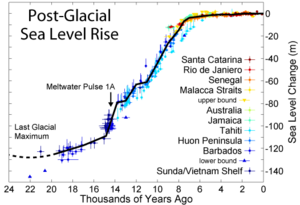

For generations, geologists have been trying to explain the obvious cyclicity of sedimentary deposits observed everywhere we look. The prevailing theories hold that this cyclicity primarily represents the response of depositional processes to the rise and fall of sea level. In the rock record, geologists see times when sea level was astoundingly low alternating with times when sea level was much higher than today, and these anomalies often appear worldwide. For instance, during the depths of the last ice age 18,000 years ago when hundreds of thousands of cubic miles of ice were stacked up on the continents as glaciers, sea level was 120 m (390 ft) lower, locations that today support coral reefs were left high and dry, and coastlines were miles farther basinward from the present-day coastline. It was during this time of very low sea level that there was a dry land connection between Asia and Alaska over which humans are believed to have migrated to North America (see Bering Land Bridge).

However, for the past 6,000 years (many centuries before the first known written records), the world's sea level has been gradually approaching the level we see today. During the previous interglacial about 120,000 years ago, sea level was for a short time about 6 m higher than today, as evidenced by wave-cut notches along cliffs in the Bahamas. There are also Pleistocene coral reefs left stranded about 3 metres above today's sea level along the southwestern coastline of West Caicos Island in the West Indies. These once-submerged reefs and nearby paleo-beach deposits are silent testimony that sea level spent enough time at that higher level to allow the reefs to grow (exactly where this extra sea water came from—Antarctica or Greenland—has not yet been determined). Similar evidence of geologically recent sea level positions is abundant around the world.

Estimates

See IPCC TAR, figure 11.4 for a graph of sea level changes over the past 140,000 years.[16]

- The 2007 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report suggested that sea levels would rise by between 190 mm (7.5 inches) and 590 mm by the end of this century.[17]

- Sea-level rise estimates from satellite altimetry since 1992 (about 2.8 mm/yr) exceed those from tide gauges. It is unclear whether this represents an increase over the last decades, variability, or problems with satellite calibration.

- Church and White (2006) report an acceleration of SLR since 1870.[2] This is a revision since 2001, when the TAR stated that measurements have detected no significant acceleration in the recent rate of sea level rise.

- Based on tide gauge data, the rate of global average sea level rise during the 20th century lies in the range 0.8 to 3.3 mm/yr, with an average rate of 1.8 mm/yr.[18]

- Recent studies of Roman wells in Caesarea and of Roman piscinae in Italy indicate that sea level stayed fairly constant from a few hundred years AD to a few hundred years ago.

- Based on geological data, global average sea level may have risen at an average rate of about 0.5 mm/yr over the last 6,000 years and at an average rate of 0.1 to 0.2 mm/yr over the last 3,000 years.

- Since the Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago, sea level has risen by over 120 m (averaging 6 mm/yr) as a result of melting of major ice sheets. A rapid rise took place between 15,000 and 6,000 years ago at an average rate of 10 mm/yr which accounted for 90 m of the rise; thus in the period since 20,000 years BP (excluding the rapid rise from 15-6 kyr BP) the average rate was 3 mm/yr.

- A significant event was Meltwater pulse 1A (mwp-1A), when sea level rose approximately 20 m over a 500 year period about 14,200 years ago. This is a rate of about 40 mm/yr. Recent studies suggest the primary source was meltwater from the Antarctic, perhaps causing the south-to-north cold pulse marked by the Southern Hemisphere Huelmo/Mascardi Cold Reversal, which preceded the Northern Hemisphere Younger Dryas

- Relative sea level rise at specific locations is often 1–2 mm/yr greater or less than the global average. Along the US mid-Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, for example, sea level is rising approximately 3 mm/yr

U. S. Tide Gauge Measurements

Tide gauges in the United States show considerable variation because some land areas are rising and some are sinking. For example, over the past 100 years, the rate of sea level rise varies from about an increase of 0.36 inches (9.1 mm) per year along the Louisiana Coast (due to land sinking), to a drop of a few inches per decade in parts of Alaska (due to post-glacial rebound). The rate of sea level rise increased during the 1993-2003 period compared with the longer-term average (1961–2003), although it is unclear whether the faster rate reflects a short-term variation or an increase in the long-term trend.[19]

Amsterdam Sea Level Measurements

The longest running sea-level measurements are recorded at Amsterdam, in the Netherlands—part of which (about 25%) lies beneath sea level, hence the name. Records from 1700 onwards can be found at http://www.pol.ac.uk/psmsl/longrecords/longrecords.html. Since 1850, a rise of approx 1.5 mm/year is shown here.

Australian Sea Level Change

The London Royal Society calculates net sea level rise in Australia at 1 mm/yr[20]—an important result for the Southern Hemisphere. The National Tidal Center also graphs 32 gauges, some since 1880, for the entire coastline[21]

Future sea level rise

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) predicted that by 2100, global warming will lead to a sea level rise of 180 to 590 mm[22], depending on which of six possible world scenarios comes to pass, and barring rapid dynamical changes in ice flow.[23] More recent research, which has observed rapid declines in ice mass balance from both Greenland and Antarctica, finds that sea-level rise by 2100 is likely to be at least twice as large as that presented by IPCC AR4, with an upper limit of about two meters.[24]

These sea level rises could lead to potentially catastrophic difficulties for shore-based communities in the next centuries: for example, many major cities such as London and New Orleans already need storm-surge defenses, and would need more if sea level rose, though they also face issues such as sinking land.[25] Sea level rise could also displace many shore-based populations: for example it is estimated that a sea level rise of just 200 mm could create 740,000 homeless people in Nigeria.[26] Maldives, Tuvalu, and other low-lying countries are among the areas that are at the highest level of risk. The UN's environmental panel has warned that, at current rates, sea level would be high enough to make the Maldives uninhabitable by 2100.[27][28]

Future sea level rise, like the recent rise, is not expected to be globally uniform (details below). Some regions show a sea-level rise substantially more than the global average (in many cases of more than twice the average), and others a sea level fall.[29] However, models disagree as to the likely pattern of sea level change.[30]

In September 2008, the Delta Commission presided by Dutch politician Cees Veerman advised in a report that The Netherlands would need a massive new building program to strengthen the country's water defenses against the anticipated effects of global warming for the next 190 years. This commission was created in September 2007, after the damage caused by Hurricane Katrina prompted reflection and preparations. Those included drawing up worst-case plans for evacuations. The plan included more than €100 billion, or $144 billion, in new spending through the year 2100 to take measures, such as broadening coastal dunes and strengthening sea and river dikes.

The commission said the country must plan for a rise in the North Sea of around 30 inches, or 80 centimeters, by 2100 and of as much as 4.25 feet, or 1.3 meters, by 2100, and 6.5-13 feet by 2200. [31]

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change results

The results from the IPCC Third Assessment Report (TAR) sea level chapter (convening authors John A. Church and Jonathan M. Gregory) are given below.

| IPCC change factors 1990-2100 | IS92a prediction | SRES prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal expansion | 110 to 430 mm | |

| Glaciers | 10 to 230 mm[32] (or 50 to 110 mm)[33] |

|

| Greenland ice | –20 to 90 mm | |

| Antarctic ice | –170 to 20 mm | |

| Terrestrial storage | –83 to 30 mm | |

| Ongoing contributions from ice sheets in response to past climate change | 0 to 55 mm | |

| Thawing of permafrost | 0 to 5 mm | |

| Deposition of sediment | not specified | |

| Total global-average sea level rise (IPCC result, not sum of above)[32] |

110 to 770 mm | 90 to 880 mm (central value of 480 mm) |

The sum of these components indicates a rate of eustatic sea level rise (corresponding to a change in ocean volume) from 1910 to 1990 ranging from –0.8 to 2.2 mm/yr, with a central value of 0.7 mm/yr. The upper bound is close to the observational upper bound (2.0 mm/yr), but the central value is less than the observational lower bound (1.0 mm/yr), i.e., the sum of components is biased low compared to the observational estimates. The sum of components indicates an acceleration of only 0.2 (mm/yr)/century, with a range from –1.1 to +0.7 (mm/yr)/century, consistent with observational finding of no acceleration in sea level rise during the 20th century. The estimated rate of sea-level rise from anthropogenic climate change from 1910 to 1990 (from modeling studies of thermal expansion, glaciers and ice sheets) ranges from 0.3 to 0.8 mm/yr. It is very likely that 20th century warming has contributed significantly to the observed sea-level rise, through thermal expansion of sea water and widespread loss of land ice.[32]

A common perception is that the rate of sea-level rise should have accelerated during the latter half of the 20th century, but tide gauge data for the 20th century show no significant acceleration. Estimates obtained are based on AOGCMs for the terms directly related to anthropogenic climate change in the 20th century, i.e., thermal expansion, ice sheets, glaciers and ice caps... The total computed rise indicates an acceleration of only 0.2 (mm/yr)/century, with a range from -1.1 to +0.7 (mm/yr)/century, consistent with observational finding of no acceleration in sea-level rise during the 20th century.[34] The sum of terms not related to recent climate change is -1.1 to +0.9 mm/yr (i.e., excluding thermal expansion, glaciers and ice caps, and changes in the ice sheets due to 20th century climate change). This range is less than the observational lower bound of sea level rise. Hence it is very likely that these terms alone are an insufficient explanation, implying that 20th century climate change has made a contribution to 20th century sea level rise.[13] Recent figures of human, terrestrial impoundment came too late for the 3rd Report, and would revise levels upward for much of the 20th century.

Uncertainties and criticisms regarding IPCC results

- Tide records with a rate of 180 mm/century going back to the 19th century show no measurable acceleration throughout the late 19th and first half of the 20th century. The IPCC attributes about 60 mm/century to melting and other eustatic processes, leaving a residual of 120 mm of 20th century rise to be accounted for. Global ocean temperatures by Levitus et al. are in accord with coupled ocean/atmosphere modelling of greenhouse warming, with heat-related change of 30 mm. Melting of polar ice sheets at the upper limit of the IPCC estimates could close the gap, but severe limits are imposed by the observed perturbations in Earth rotation. (Munk 2002)

- By the time of the IPCC TAR, attribution of sea-level changes had a large unexplained gap between direct and indirect estimates of global sea-level rise. Most direct estimates from tide gauges give 1.5–2.0 mm/yr, whereas indirect estimates based on the two processes responsible for global sea-level rise, namely mass and volume change, are significantly below this range. Estimates of the volume increase due to ocean warming give a rate of about 0.5 mm/yr and the rate due to mass increase, primarily from the melting of continental ice, is thought to be even smaller. One study confirmed tide gauge data is correct, and concluded there must be a continental source of 1.4 mm/yr of fresh water. (Miller 2004)

- From (Douglas 2002): "In the last dozen years, published values of 20th century GSL rise have ranged from 1.0 to 2.4 mm/yr. In its Third Assessment Report, the IPCC discusses this lack of consensus at length and is careful not to present a best estimate of 20th century GSL rise. By design, the panel presents a snapshot of published analysis over the previous decade or so and interprets the broad range of estimates as reflecting the uncertainty of our knowledge of GSL rise. We disagree with the IPCC interpretation. In our view, values much below 2 mm/yr are inconsistent with regional observations of sea-level rise and with the continuing physical response of Earth to the most recent episode of deglaciation."

- The strong 1997-1998 El Niño caused regional and global sea level variations, including a temporary global increase of perhaps 20 mm. The IPCC TAR's examination of satellite trends says the major 1997/98 El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) event could bias the above estimates of sea-level rise and also indicate the difficulty of separating long-term trends from climatic variability.[34]

Glacier contribution

It is well known that glaciers are subject to surges in their rate of movement with consequent melting when they reach lower altitudes and/or the sea. The contributors to Annals of Glaciology [2], Volume 36 [3] (2003) discussed this phenomenon extensively and it appears that slow advance and rapid retreat have persisted throughout the mid to late Holocene in nearly all of Alaska's glaciers. Historical reports of surge occurrences in Iceland's glaciers go back several centuries. Thus rapid retreat can have several other causes than CO2 increase in the atmosphere.

The results from Dyurgerov show a sharp increase in the contribution of mountain and subpolar glaciers to sea level rise since 1996 (0.5 mm/yr) to 1998 (2 mm/yr) with an average of approx. 0.35 mm/yr since 1960.[35]

Of interest also is Arendt et al.,[36] who estimate the contribution of Alaskan glaciers of 0.14±0.04 mm/yr between the mid 1950s to the mid 1990s increasing to 0.27 mm/yr in the middle and late 1990s.

Greenland contribution

Krabill et al.[37] estimate a net contribution from Greenland to be at least 0.13 mm/yr in the 1990s. Joughin et al.[38] have measured a doubling of the speed of Jakobshavn Isbræ between 1997 and 2003. This is Greenland's largest outlet glacier; it drains 6.5% of the ice sheet, and is thought to be responsible for increasing the rate of sea level rise by about 0.06 millimetres per year, or roughly 4% of the 20th century rate of sea level increase.[39] In 2004, Rignot et al.[40] estimated a contribution of 0.04±0.01 mm/yr to sea level rise from southeast Greenland.

Rignot and Kanagaratnam[41] produced a comprehensive study and map of the outlet glaciers and basins of Greenland. They found widespread glacial acceleration below 66 N in 1996 which spread to 70 N by 2005; and that the ice sheet loss rate in that decade increased from 90 to 200 cubic km/yr; this corresponds to an extra 0.25 to 0.55 mm/yr of sea level rise.

In July 2005 it was reported[42] that the Kangerdlugssuaq glacier, on Greenland's east coast, was moving towards the sea three times faster than a decade earlier. Kangerdlugssuaq is around 1,000 m thick, 7.2 km (4.5 miles) wide, and drains about 4% of the ice from the Greenland ice sheet. Measurements of Kangerdlugssuaq in 1988 and 1996 showed it moving at between 5 and 6 km/yr (3.1 to 3.7 miles/yr) (in 2005 it was moving at 14 km/yr [8.7 miles/yr]).

According to the 2004 Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, climate models project that local warming in Greenland will exceed 3° Celsius during this century. Also, ice sheet models project that such a warming would initiate the long-term melting of the ice sheet, leading to a complete melting of the Greenland ice sheet over several millennia, resulting in a global sea level rise of about seven metres.[43]

Antarctic contribution

On the Antarctic continent itself, the large volume of ice present stores around 70 % of the world's fresh water.[44] This ice sheet is constantly gaining ice from snowfall and losing ice through outflow to the sea. West Antarctica is currently experiencing a net outflow of glacial ice, which will increase global sea level over time. A review of the scientific studies looking at data from 1992 to 2006 suggested a net loss of around 50 Gigatonnes of ice per year was a reasonable estimate (around 0.14 mm of sea level rise),[45] although significant acceleration of outflow glaciers in the Amundsen Sea Embayment could have more than doubled this figure for the year 2006.[46]

East Antarctica is a cold region with a ground base above sea level and occupies most of the continent. This area is dominated by small accumulations of snowfall which becomes ice and thus eventually seaward glacial flows. The mass balance of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet as a whole is thought to be slightly positive (lowering sea level) or near to balance.[45][46] However, increased ice outflow has been suggested in some regions.[46][47]

Effects of snowline and permafrost

The snowline altitude is the altitude of the lowest elevation interval in which minimum annual snow cover exceeds 50%. This ranges from about 5,500 metres above sea-level at the equator down to sea-level at about 65° N&S latitude, depending on regional temperature amelioration effects. Permafrost then appears at sea-level and extends deeper below sea-level pole-wards. The depth of permafrost and the height of the ice-fields in both Greenland and Antarctica means that they are largely invulnerable to rapid melting. Greenland Summit is at 3,200 metres, where the average annual temperature is minus 32 °C. So even a projected 4 °C rise in temperature leaves it well below the melting point of ice. Frozen Ground 28, December 2004, has a very significant map of permafrost affected areas in the Arctic. The continuous permafrost zone includes all of Greenland, the North of Labrador, NW Territories, Alaska north of Fairbanks, and most of NE Siberia north of Mongolia and Kamchatka. Continental ice above permafrost is very unlikely to melt quickly. As most of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets lie above the snowline and/or base of the permafrost zone, they cannot melt in a timeframe much less than several millennia; therefore they are unlikely to contribute significantly to sea-level rise in the coming century.

Polar ice

The sea level will rise above its current level if more polar ice melts. However, compared to the heights of the ice ages, today there are very few continental ice sheets remaining to be melted. It is estimated that Antarctica, if fully melted, would contribute more than 60 metres of sea level rise, and Greenland would contribute more than 7 metres. Small glaciers and ice caps on the margins of Greenland and the Antarctic Peninsula might contribute about 0.5 metres. While the latter figure is much smaller than for Antarctica or Greenland it could occur relatively quickly (within the coming century) whereas melting of Greenland would be slow (perhaps 1,500 years to fully deglaciate at the fastest likely rate) and Antarctica even slower.[11] However, this calculation does not account for the possibility that as meltwater flows under and lubricates the larger ice sheets, they could begin to move much more rapidly towards the sea.[48][49]

In 2002, Rignot and Thomas[50] found that the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets were losing mass, while the East Antarctic ice sheet was probably in balance (although they could not determine the sign of the mass balance for The East Antarctic ice sheet). Kwok and Comiso (J. Climate, v15, 487-501, 2002) also discovered that temperature and pressure anomalies around West Antarctica and on the other side of the Antarctic Peninsula correlate with recent Southern Oscillation events.

In 2004 Rignot et al.[40] estimated a contribution of 0.04±0.01 mm/yr to sea level rise from South East Greenland. In the same year, Thomas et al.[51] found evidence of an accelerated contribution to sea level rise from West Antarctica. The data showed that the Amundsen Sea sector of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet was discharging 250 cubic kilometres of ice every year, which was 60% more than precipitation accumulation in the catchment areas. This alone was sufficient to raise sea level at 0.24 mm/yr. Further, thinning rates for the glaciers studied in 2002-2003 had increased over the values measured in the early 1990s. The bedrock underlying the glaciers was found to be hundreds of metres deeper than previously known, indicating exit routes for ice from further inland in the Byrd Subpolar Basin. Thus the West Antarctic ice sheet may not be as stable as has been supposed.

In 2005 it was reported that during 1992-2003, East Antarctica thickened at an average rate of about 18 mm/yr while West Antarctica showed an overall thinning of 9 mm/yr. associated with increased precipitation. A gain of this magnitude is enough to slow sea-level rise by 0.12±0.02 mm/yr.[52]

Effects of sea level rise

Based on the projected increases stated above, the IPCC TAR WG II report notes that current and future climate change would be expected to have a number of impacts, particularly on coastal systems.[53] Such impacts may include increased coastal erosion, higher storm-surge flooding, inhibition of primary production processes, more extensive coastal inundation, changes in surface water quality and groundwater characteristics, increased loss of property and coastal habitats, increased flood risk and potential loss of life, loss of nonmonetary cultural resources and values, impacts on agriculture and aquaculture through decline in soil and water quality, and loss of tourism, recreation, and transportation functions.

There is an implication that many of these impacts will be detrimental—especially for the three-quarters of the world's poor who depend on agriculture systems.[54] The report does, however, note that owing to the great diversity of coastal environments; regional and local differences in projected relative sea level and climate changes; and differences in the resilience and adaptive capacity of ecosystems, sectors, and countries, the impacts will be highly variable in time and space.

Statistical data on the human impact of sea level rise is scarce. A study in the April, 2007 issue of Environment and Urbanization reports that 634 million people live in coastal areas within 30 feet (9.1 m) of sea level. The study also reported that about two thirds of the world's cities with over five million people are located in these low-lying coastal areas. The IPCC report of 2007 estimated that accelerated melting of the Himalayan ice caps and the resulting rise in sea levels would likely increase the severity of flooding in the short-term during the rainy season and greatly magnify the impact of tidal storm surges during the cyclone season. A sea-level rise of just 400 mm in the Bay of Bengal would put 11 percent of the Bangladesh's coastal land underwater, creating 7 to 10 million climate refugees.

Island nations

IPCC assessments suggest that deltas and small island states are particularly vulnerable to sea level rise caused by both thermal expansion and ocean volume. Relative sea level rise (mostly caused by subsidence) is currently causing substantial loss of lands in some deltas.[55] Sea level changes have not yet been conclusively proven to have directly resulted in environmental, humanitarian, or economic losses to small island states, but the IPCC and other bodies have found this a serious risk scenario in coming decades.[56]

Many media reports have focused the island nations of the Pacific, notably the Polynesian islands of Tuvalu, which based on more severe flooding events in recent years, was thought to be "sinking" due to sea level rise.[57] A scientific review in 2000 reported that based on University of Hawaii gauge data, Tuvalu had experienced a negligible increase in sea-level of 0.07 mm a year over the past two decades, and that ENSO had been a larger factor in Tuvalu's higher tides in recent years.[58] A subsequent study by John Hunter from the University of Tasmania, however, adjusted for ENSO effects and the movement of the gauge (which was thought to be sinking). Hunter concluded that Tuvalu had been experiencing sea-level rise of about 1.2 mm per year.[58][59] The recent more frequent flooding in Tuvalu may also be due to an erosional loss of land during and following the actions of 1997 cyclones Gavin, Hina, and Keli.[60]

Reuters has reported other Pacific islands are facing a severe risk including Tegua island in Vanuatu. Claims that Vanuatu data shows no net sea level rise, are not substantiated by tide gauge data. Vanuatu tide gauge data show a net rise of ~50 mm from 1994-2004. Linear regression of this short time series suggests a rate of rise of ~7 mm/y, though there is considerable variability and the exact threat to the islands is difficult to assess using such a short time series.

Numerous options have been proposed that would assist island nations to adapt to rising sea level.[61]

Satellite sea level measurement

Sea level rise estimates from satellite altimetry are 3.1 ± 0.4 mm/yr for 1993-2003 (Leuliette et al. (2004)). This exceeds those from tide gauges. It is unclear whether this represents an increase over the last decades; variability; true differences between satellites and tide gauges; or problems with satellite calibration.[34] Knowing the current altitude of a satellite which can measure sea level to a precision of about 20 millimetres (e.g. the Topex/Poseidon system) is primarily complicated by orbital decay and the difference between the assumed orbit and the earth geoid [62]. This problem is partially corrected by regular re-calibration of satellite altimeters from land stations whose height from MSL is known by surveying. Over water, the height is calibrated from tide gauge data which is needed to correct for tides and atmospheric effects on sea level.

See also

- 8.2 kiloyear event

- Antarctic Cold Reversal

- Climate of Antarctica

- Global Warming

- Transgression (geology)

- Older Peron transgression

- Retreat of glaciers since 1850

Notes

- ↑ Bruce C. Douglas (1997). "Global Sea Rise: A Redetermination". Surveys in Geophysics 18: 279–292. doi:10.1023/A:1006544227856.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Church, John; White, Neil (January 6, 2006), "A 20th century acceleration in global sea-level rise", Geophysical Research Letters 33: L01602, doi:10.1029/2005GL024826, L01602, http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/2006/2005GL024826.shtml, retrieved 2010-05-17 pdf is here

- ↑ Chambers, D. P.; Ries, J. C.; Urban, T. J. (2003). "Calibration and Verification of Jason-1 Using Global Along-Track Residuals with TOPEX". Marine Geodesy 26: 305. doi:10.1080/714044523.

- ↑ Bindoff, NL et al.. "Observations: Oceanic Climate Change and Sea Level". Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/Report/AR4WG1_Print_Ch05.pdf.

- ↑ Nathaniel L. Bindoff, Jürgen Willebrand et al. (2007). "Observations: Oceanic Climate Change and Sea Level". In Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.: Cambridge University Press. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg1/ar4-wg1-chapter5.pdf.

- ↑ Meehl, G.A., T.F. Stocker, W.D. Collins, P. Friedlingstein, A.T. Gaye, J.M. Gregory, A. Kitoh, R. Knutti, J.M. Murphy, A. Noda, S.C.B. Raper,, I.G. Watterson, A.J. Weaver and Z.-C. Zhao, 2007: Global Climate Projections. In: Climate, Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S.,D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Projections of Global Average Sea Level Change for the 21st Century Chapter 10, p 820

- ↑ http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/Report/AR4WG1_Print_Ch10.pdf

- ↑ "IPCC AR4 Chapter 5". IPCC. 2007. pp. 409. http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/Report/AR4WG1_Print_Ch05.pdf. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ Pfeffer, Wt; Harper, Jt; O'Neel, S (Sep 2008). "Kinematic constraints on glacier contributions to 21st-century sea-level rise.". Science (New York, N.Y.) 321 (5894): 1340–3. doi:10.1126/science.1159099. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18772435.

- ↑ Yale Environment 360, quoting Danish Meteorological Institute

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Some physical characteristics of ice on Earth". Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/412.htm#tab113.

- ↑ Geologic Contral on Fast Ice Flow - West Antarctic Ice Sheet

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/428.htm. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ "Ocean Surface Topography from Space". NASA/JPL. http://topex-www.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/topex.html.

- ↑ "Ocean Surface Topography from Space". NASA/JPL. http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/jason-1.html.

- ↑ "IPCC TAR, figure 11.4". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/fig11-4.htm. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ Americas on alert for sea level rise

- ↑ "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/422.htm#tab119. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency "Sea Level Changes"

- ↑ LANDMARK STUDY CONFIRMS RISING AUSTRALIAN SEA LEVEL

- ↑ Australian Mean Sea Level Survey 2003

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). "Coastal Systems and Low-lying Areas, Table 6.3" (pdf). Coastal Systems and Low-lying Areas. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg2/ar4-wg2-chapter6.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). "Projected global average surface warming and sea level rise at the end of the 21st century, Table SPM.3" (pdf). Projected global average surface warming and sea level rise at the end of the 21st century.. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg1/ar4-wg1-spm.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ I. Allison, N.L. Bindoff, R.A. Bindschadler, P.M. Cox, N. de Noblet, M.H. England, J.E. Francis, N. Gruber, A.M. Haywood, D.J. Karoly, G. Kaser, C. Le Quéré, T.M. Lenton, M.E. Mann, B.I. McNeil, A.J. Pitman, S. Rahmstorf, E. Rignot, H.J. Schellnhuber, S.H. Schneider, S.C. Sherwood, R.C.J. Somerville, K. Steffen, E.J. Steig, M. Visbeck, A.J. Weaver (2009). "Copenhagen Diagnosis". The Copenhagen Diagnosis, 2009: Updating the World on the Latest Climate Science. http://www.copenhagendiagnosis.org/read/default.html. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Church, J.A. and J.M. Gregory. "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/index.htm. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ Klaus Paehler. "Nigeria in the Dilemma of Climate Change". http://www.kas.de/proj/home/pub/33/2/dokument_id-11468/index.html. Retrieved 2008-11-04.,

- ↑ Megan Angelo (1 May 2009). "Honey, I Sunk the Maldives: Environmental changes could wipe out some of the world's most well-known travel destinations". http://travel.yahoo.com/p-interests-27384279;_ylc=X3oDMTFxcWIyczFpBF9TAzI3MTYxNDkEX3MDMjcxOTQ4MQRzZWMDZnAtdG9kYXltb2QEc2xrA21hbGRpdmVzLTQtMjgtMDk-.

- ↑ Kristina Stefanova (19 April 2009). "Climate refugees in Pacific flee rising sea". http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2009/apr/19/rising-sea-levels-in-pacific-create-wave-of-migran/.

- ↑ "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/432.htm. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/fig11-13.htm. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ "Dutch draw up drastic measures to defend coast against rising seas"

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/409.htm. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/434.htm#11542. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/426.htm#fig1110. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ Dyurgerov, Mark. 2002. Glacier Mass Balance and Regime: Data of Measurements and Analysis. INSTAAR Occasional Paper No. 55, ed. M. Meier and R. Armstrong. Boulder, CO: Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado. Distributed by National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, CO. A shorter discussion is at [1]

- ↑ Arendt, AA; et al. (July 2002). "Rapid Wastage of Alaska Glaciers and Their Contribution to Rising Sea Level". Science 297 (5580): 382–386. doi:10.1126/science.1072497. PMID 12130781.

- ↑ Krabill, W; et al. (21 July 2000). "Greenland Ice Sheet: High-Elevation Balance and Peripheral Thinning". Science 289 (5478): 428–430. doi:10.1126/science.289.5478.428. PMID 10903198.

- ↑ Joughin, I; et al. (December 2004). "Large fluctuations in speed on Greenland's Jakobshavn Isbræ glacier". Nature 432 (7017): 608–610. doi:10.1038/nature03130. PMID 15577906.

- ↑ Report shows movement of glacier has doubled speed | SpaceRef - Your Space Reference

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Rignot, E.; et al. (2004). "Rapid ice discharge from southeast Greenland glaciers". Geophysical Research Letters 31: L10401. doi:10.1029/2004GL019474.

- ↑ Rignot, E; Kanagaratnam (2006). "Changes in the Velocity Structure of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Science 311 (5763): 986 et seq.. doi:10.1126/science.1121381. PMID 16484490. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/311/5763/986?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&fulltext=luckman&searchid=1140284328766_4322&FIRSTINDEX=0&journalcode=sci.

- ↑ Connor, Steve (2005-07-25). "Melting Greenland glacier may hasten rise in sea level". The Independent (London). http://news.independent.co.uk/world/environment/article301493.ece. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/corporate/pressoffice/adcc/BookCh4Jan2006.pdf

- ↑ "How Stuff Works: polar ice caps". howstuffworks.com. http://science.howstuffworks.com/question473.htm. Retrieved 2006-02-12.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Shepherd A., Wingham D, (2007). "Recent sea-level contributions of the Antarctic and Greenland Ice Sheets". Science 315: 1529–1532. doi:10.1126/science.1136776.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Rignot E., Bamber J.L., van den Broeke, M.R., Davis C., Li Y., van de Berg W.J., van Meijgaard E. (2008). "Recent Antarctic ice mass loss from radar interferometry and regional climate modelling". Nature Geoscience 1: 106–110. doi:10.1038/ngeo102.

- ↑ Chen, J.L., Wilson C.R., Tapley B.D., Blankenship D., Young D. (2007). "Antarctic regional ice loss rates from GRACE". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 266: 140–148. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.10.057.

- ↑ Zwally H.J. et al. (2002). "Surface Melt-Induced Acceleration of Greenland Ice-Sheet Flow". Science 297 (5579): 218–222. doi:10.1126/science.1072708. PMID 12052902. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/297/5579/218.

- ↑ "Greenland Ice Sheet flows faster during summer melting". Goddard Space Flight Center (press release). 2006-06-02. http://www.gsfc.nasa.gov/topstory/20020606greenland.html.

- ↑ Rignot, E; Thomas (2002). "Mass Balance of Polar Ice Sheets". Science 297 (5586): 1502–1506. doi:10.1126/science.1073888. PMID 12202817.

- ↑ Thomas, R; et al. (2004). "Accelerated Sea-Level Rise from West Antarctica". Science 306 (5694): 255–258. doi:10.1126/science.1099650. PMID 15388895.

- ↑ Davis, Curt H.; Yonghong Li, Joseph R. McConnell, Markus M. Frey, Edward Hanna (24 June 2005). "Snowfall-Driven Growth in East Antarctic Ice Sheet Mitigates Recent Sea-Level Rise". Science 308 (5730): 1898–1901. doi:10.1126/science.1110662. PMID 15905362.

- ↑ "Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg2/292.htm. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ "Climate Shocks: Risk and Vulnerability in an Unequal World." Human Development report 2007/2008. hdr.undp.org/media/hdr_20072008_summary_english.pdf

- ↑ Tidwell, Mike (2006). The Ravaging Tide: Strange Weather, Future Katrinas, and the Coming Death of America's Coastal Cities. Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-9470-X.

- ↑ The Future Oceans - Warming Up, Rising High, Turning Sour

- ↑ Levine, Mark (December 2002). "Tuvalu Toodle-oo". Outside Magazine. http://outside.away.com/outside/features/200212/200212_tuvalu_1.html. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Patel, Samir S. (April 5, 2006). "A Sinking Feeling". Nature. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7085/full/440734a.html. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ Hunter, J.A. (August 12, 2002). "A Note on Relative Sea Level Rise at Funafuti, Tuvalu" (PDF). http://staff.acecrc.org.au/~johunter/tuvalu.pdf.

- ↑ Field, Michael J. (December 2001). "Sea Levels Are Rising". Pacific Magazine. http://www.pacificislands.cc/pm122001/pmdefault.php?urlarticleid=0009. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ "Policy Implications of Sea Level Rise: The Case of the Maldives.". Proceedings of the Small Island States Conference on Sea Level Rise. November 14–18, 1989. Male, Republic of Maldives. Edited by Hussein Shihab. http://papers.risingsea.net/Maldives/Small_Island_States_3.html. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ↑ http://ibis.grdl.noaa.gov/SAT/pubs/papers/2001_Cheney_Encycl.pdf

References

- Cazenave, A.; Nerem, R. S. (2004). "Present-day sea level change: Observations and causes". Rev. Geophys 42: RG3001. doi:10.1029/2003RG000139.

- Emery, K.O., and D. G. Aubrey (1991). Sea levels, land levels, and tide gauges. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-97449-0.

- "Sea Level Variations of the United States 1854-1999" (PDF). NOAA Technical Report NOS CO-OPS 36. http://co-ops.nos.noaa.gov/publications/techrpt36doc.pdf. Retrieved 20 February 2005.

- Clark, P. U., Mitrovica, J. X., Milne, G. A. & Tamisiea (2002). "Sea-Level Fingerprinting as a Direct Test for the Source of Global Meltwater Pulse 1A". Science 295 (5564): 2438–2441. doi:10.1126/science.1069017. PMID 11896236.

- Eelco J. Rohling, Robert Marsh, Neil C. Wells, Mark Siddall and Neil R. Edwards (2004). "Similar meltwater contributions to glacial sea level changes from Antarctic and northern ice sheets". Nature 430 (August 26): 1016–1021. doi:10.1038/nature02859.

- Walter Munk (2002). "Twentieth century sea level: An enigma". Geophysics 99 (10): 6550–6555.

- Menefee, Samuel Pyeatt (1991). "Half Seas Over: The Impact of Sea Level Rise on International Law and Policy". U.C.L.A. Journal of Environmental Law & Policy 9: 175–218.

- Laury Miller and Bruce C. Douglas (2004). "Mass and volume contributions to twentieth-century global sea level rise". Nature 428 (6981): 406–409. doi:10.1038/nature02309. PMID 15042085.

- Bruce C. Douglas and W. Richard Peltier (2002). "The Puzzle of Global Sea-Level Rise" (– Scholar search). Physics Today 55 (3): 35–41. doi:10.1063/1.1472392. http://www.aip.org/pt/vol-55/iss-3/p35.html. Retrieved 24 March 2005.

- B. C. Douglas (1992). "Global sea level acceleration". J. Geophys. Res. 7 (c8): 12699. doi:10.1029/92JC01133.

- Warrick, R. A., C. L. Provost, M. F. Meier, J. Oerlemans, and P. L. Woodworth (1996). "Changes in sea level". In Houghton, John Theodore. Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 359–405. ISBN 0-521-56436-0.

- R. Kwok, J. C. Comiso (2002). "Southern Ocean Climate and Sea Ice Anomalies Associated with the Southern Oscillation" (PDF). Journal of Climate 15 (5): 487–501. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2002)015<0487:SOCASI>2.0.CO;2. http://neptune.gsfc.nasa.gov/publications/pdf/pubs2002/2_Southern_Ocean_Climate.pdf.

- Colorado Center for Astrodynamics Research, "Mean Sea Level" Accessed December 19, 2005

- Fahnestock, Mark (December 4, 2004), "Report shows movement of glacier has doubled speed", University of New Hampshire press release. Accessed December 19, 2005

- Leuliette, E.W., R.S. Nerem, and G.T. Mitchum (2004). "Calibration of TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason Altimeter Data to Construct a Continuous Record of Mean Sea Level Change". Marine Geodesy 27 (1-2).

- National Snow and Ice Data Center (March 14, 2005), "Is Global Sea Level Rising?". Accessed December 19, 2005

- INQUA commission on Sea Level Changes and Coastal Evolution. "IPCC again" (PDF). http://web.archive.org/web/20040725130615/http://www.pog.su.se/sea/HP-14.+IPCC-3.pdf. Retrieved 2004-07-25.

- Connor, Steve (2005-07-25). "Independent Online Edition". The Independent (London). http://news.independent.co.uk/world/environment/article301493.ece. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- Maumoon Abdul Gayoom. "Address by his Excellency Mr. Maumoon Abdul Gahoom, President of the Republic of Maldives, at thenineteenth special session of the United Nations General Assembly for the purpose of an overall review and appraisal of theimplementation of agenda 21 - June 24, 1997". http://www.un.int/maldives/ungass.htm. Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- Pilkey, Orrin and Robert Young, The Rising Sea, Shearwater, July 2009 ISBN 978-1597261913

External links

- "Climate change threatening the Southern Ocean". http://csiro.au/multimedia/Climate-change-threat-to-Southern-Ocean.html.

- Sea Level Rise:Understanding the past - Improving projections for the future

- Providing new homes for climate exiles Sujatha Byravan and Sudhir Chella Rajan, 2006

- New perspectives for the future of the Maldives Nils-Axel Mörner, Michael Tooley, Göran Possnert, 2004

- "Physical Agents of Land Loss: Relative Sea Level". An Overview of Coastal Land Loss: With Emphasis on the Southeastern United States. http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2003/of03-337/global.html. Retrieved 14 February 2005.

- Changes in the Earth's shorelines during the past 20 kyr caused by the deglaciation of the Late Pleistocene ice sheets, from the Permanent Service for Mean Sea Level

- Indigenous Aboriginal Australian Perspective on Sea Level Changes: Video

- Includes picture of sea level for past 20 kyr based on barbados coral record

- Global sea level change: Determination and interpretation

- Sea level rise FAQ (1997)

- The Global Sea Level Observing System (GLOSS)

- The GLOSS Station Handbook

- "Sea Level Rise Reports". US Environmental Protection Agency website. http://www.epa.gov/globalwarming/sealevelrise.

- The Sinking of Tuvalu

- Center for the Remote Sensing of Ice Sheets - Maps, Animations, GIS Layers

- Tides and Sea Level Rise Model

- "University of Colorado at Boulder Sea Level Change". http://sealevel.colorado.edu/.

- Maps that show a Rise in Sea Levels

- Sea Level Rise of up to 14m - meltdown of Greenlandic ice shield

- World Maps for a sea level rise in 60m - meltdown of the antarctic ice shield

- Hazard map showing variable sea level rise and earthquake impacts, developed by CyArk to demonstrate potential impact of climate change (and earthquakes) on World Heritage Sites

- Sea Levels Online: National Ocean Service (CO-OPS), displays local sea level rise and sea level trends via a map interface

- Sea Level Rise Planning Maps County and state scale maps showing which lands below 5 meters are likely and unlikely to be protected from a rising sea, according to study funded by US Environmental Protection Agency.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||